Part one: 5 plants toxic to horses

Get the veterinary lowdown on five plants toxic to horses, where they're found, and the consequences of a horse ingesting them.

Alan Copson/Getty Images

Maple (Acer spp.)

Where it's found: Thirteen species of maple trees are found throughout the Northern Hemisphere, with a larger distribution in the eastern United States and Canada. The red maple (Acer rubrum) is among the most common, as are the sugar maple (Acer saccharum), silver maple (Acer saccharinum), and box elder (Acer negundo). Only a few species have been associated with the development of clinical signs.

The toxin and how it works: The toxin is unknown but it damages the red blood cells, making them unable to carry oxygen.

Threat to horses:

- Most of the case reports and experimental studies are specific to the red maple tree. Other species, especially hybrid species with Acer rubrum in the lineage, may be associated with intoxication. Silver and sugar maples also have been implicated by some research scientists; box elder has not.

- Ingestion of dry or wilted leaves causes signs; ingestion of fresh leaves does not.

- Dry and wilted leaves may remain toxic for up to four weeks, but generally do not retain their toxicity over the winter.

- Generally, leaves dropped after Sept. 15 are considered more toxic, but wilted leaves from branches dropped during summer storms may be just as harmful.

- It takes about 1.5 to 2 lbs of dried or wilted leaves per 1,000 lbs of a horse's body weight to cause clinical signs. All organ systems in a horse's body are affected by the blood cells' lack of oxygen. The kidneys and liver may be harmed by the red blood cell breakdown products.

Signs: These can occur as early as a few hours after ingestion or be delayed for four to five days. Depression, lethargy, and anorexia usually occur first and are followed by reddish-brown urine and pale yellowish gums and mucous membranes. Later signs include dark-brown muddy gums and mucous membranes, difficulty breathing, inability to rise, and death.

Treatment: Use activated charcoal and mineral oil to decontaminate. Aggressive IV fluids to correct dehydration and protect the kidneys as well as blood transfusions, ascorbic acid (Vitamin C), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and corticosteroids may all be necessary.

Prognosis: Good if animals are treated before signs begin. Once evidence of red blood cell damage occurs, aggressive in-hospital treatment will be needed for survival.

Darlyne A. Murawsk/Michele Constantini/Pete Saloutos/Getty Images

Foxglove (Digitalis spp.), oleander (Nerium oleander), rhododendron (Rhododendron spp.)

Where they're found: Each of these plants is found to some extent throughout the United States. Different cultivars of foxglove and rhododendron grow and overwinter in just about every state. Oleander is not hardy enough to overwinter in northern climates, but it's often found as a houseplant or ornamental container-grown plant.

The toxin and how it works: Foxglove, oleander, and rhododendron contain toxins known as cardenolides or cardiac glycosides. Cardenolides interfere with the electrical conductivity of the heart, resulting in irregularities in heart rate and rhythm.

Threat to horses:

- Ingestion of any of these plants is associated with death in horses.

- Cardenolide concentrations are found in all parts of the plant but are highest in the fruit, flowers, and immature leaves. Dried leaves retain their toxicity.

- Oleander: Ingestion of 30 to 40 leaves is deadly.

- Foxglove: Ingestion of an estimated 100 to 120 g (3 to 4 oz) of fresh leaves results in clinical signs and death.

- Rhododendron: Toxic dose in horses is not well established, but ingestion of 1 to 2 lbs of green leaves has resulted in signs.

Signs: Signs generally begin just a few hours after ingestion, and most horses are simply found dead. Other early signs include weakness; edema of the head, neck, and eyes; and a slow heart rate that progresses to irregularity. Seizures and inability to rise often occur before death.

Treatment: Rapid development of illness and signs generally make treatment impossible. Veterinarians can use activated charcoal and mineral oil to decontaminate if done so early after ingestion. Other drugs such as atropine and lidocaine that focus on specific cardiac conduction abnormalities may be useful in hospitalized cases. Digoxin-specific Fab fragments have been used successfully in small animals but are cost-prohibitive in horses.

Prognosis: Very poor once signs have developed. Early and aggressive therapy before the appearance of clinical signs improves the prognosis.

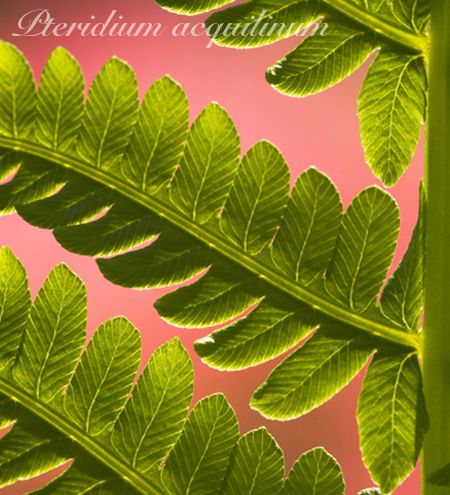

Tony Sweet/Getty Images

Bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum)

Where it's found: Bracken fern is found throughout the United States in open pastures and woodlands. It prefers moist, acidic soils.

The toxin and how it works: Bracken fern contains a type I thiaminase enzyme. It works by degrading or destroying thiamine (Vitamin B1) and creating a thiamine analog (fake thiamine) that interferes with nerve function and other bodily processes.

Threat to horses:

- Thiamine is necessary for nerve function. Low thiamine can cause the development of neurological disease.

- Both fresh and dried bracken fern is toxic if ingested.

- Some horses develop a taste for bracken fern and seek it out in the pasture and hay.

- Horses must consume large amounts of bracken fern for days to weeks before signs develop. If the plant comprises 20% to 25% of their diet, signs develop in about three weeks. If it comprises 100% of their diet, signs occur in seven to 10 days.

Signs: Signs are related to neurological dysfunction and include depression, blindness, gait abnormalities, muscle twitching, and seizures.

Treatment: Administer IV or IM thiamine for days to weeks. Other treatment is primarily supportive and includes NSAIDs, IV fluids, and drugs to prevent seizures.

Prognosis: Generally very good if treatment is begun before neurological problems develop. The onset of seizures and blindness is associated with a poor prognosis.

Matthew Ward/Getty Images

Black walnut (Juglans nigra)

Where it's found: Black walnut trees have been cultivated in the United States since 1868. They are commonly found in the eastern half of the United States except the northernmost border.

The toxin and how it works: The toxin is unknown. Many believe that juglone, present in black walnut roots and leaves, is the culprit, but scientists are unable to reproduce toxicosis by oral or dermal exposure to juglone.

Threat to horses:

- Black walnut shavings are harmful if ingested; leaves, bark, flowers, and nuts are not.

- Black walnut shavings, often purchased from furniture manufacturers, should not be used as bedding for horses. Examine new bedding that comes from an unknown source for the presence of black walnut shavings, which are much blacker in color than pine shavings.

- Horses placed on bedding composed of as little as 20% fresh black walnut shavings made from either new or old wood develop laminitis (founder) within just a few hours.

- Early removal of the horse from the bedding generally results in cessation of signs, but laminitis may continue unabated.

Signs:

- Early: Depression, limb edema, stiff gait, laminitis

- Mid: Colic, increased body temperature

- Late: Rotation of coffin bone (severe laminitis)

Treatment: Removal of the horses from the shavings as soon as signs are noticed often stops the progression of laminitis. Wash the horse's feet and limbs with cold water to remove any remaining shavings and help decrease signs of laminitis. Further treatment is based on the signs and generally includes an NSAID-such as flunixin or phenylbutazone-as well as mineral oil and good farrier care.

Prognosis: Generally very good if horse is removed within a few hours of exposure. Once laminitis develops, the prognosis for a full recovery decreases.

Robert and Jean Polluck/Getty Images

Tansy ragwort (Senecio spp.)

Where it's found: More than 70 different species of Senecio are present in the United States. This daisy-like weed is found in hay fields, pastures, ditches, and other unimproved areas.

What is the toxin and how does it work?Senecio species plants contain pyrrolizidine alkaloids, which are metabolized to pyrroles in the liver. Pyrroles inhibit cellular division, resulting in production of abnormal liver cells (megalocytes). As the megalocytes die, they are replaced with fibrotic tissue. Not all Senecio species have the same amount of toxin but all contain at least some concentration of pyrrolizidine alkaloids and all are considered harmful.

Threat to horses:

- Both fresh and dried plants are toxic if ingested.

- The plant is not particularly palatable, and most cases occur on overgrazed pastures or in the spring when green grass is scarce.

- Pyrrolizidine alkaloids are most harmful to a horse's liver.

- Damage to the liver accumulates over time and is irreversible.

- Signs generally develop after a total ingestion of 50 to 150 lbs, or about 1% to 5% of a horse's body weight, for several weeks.

Signs: Generally aren't present until the liver has failed. Once the liver fails, anorexia, weight loss, photosensitization, depression, blindness, unusual behaviors, and jaundice swiftly follow.

Treatment: There is no treatment once signs are present. If ingestion is suspected and complete liver failure has not developed, supportive care is recommended, but the horse may never return to its previous healthy state. Electrolytes, IV fluids, glucose, and B vitamins are useful, as is protecting the horse from the sun.

Prognosis: Very poor to fatal once liver failure has occurred. Poor for cases of suspected ingestion that are caught earlier.

Dr. Hovda is director of veterinary services at SafetyCall International and Pet Poison Helpline in Bloomington, Minn.

Pet Poison Helpline is a service available 24 hours, seven days a week for pet owners and veterinary team members who require assistance treating a potentially poisoned pet and can provide treatment advice for poisoning cases of all species, including dogs, cats, birds, small mammals, large animals, and exotic species. As the most cost-effective option for animal poison control care, Pet Poison Helpline's fee of $35 per incident includes follow-up consultation for the duration of the poisoning case. It is available in North America by calling 800-213-6680. Click here for additional information.