Fluid therapy in small animals: The veterinary technician's role

It is crucial that technicians understand why fluids are essential, the different types of fluids available, and how to provide them.

Being able to administer fluids to veterinary patients is an important part of providing optimal care. It is crucial that technicians understand why fluids are essential, the different types of fluids available, and how to provide them. This article focuses on how to administer the fluids. For information on other aspects of fluid therapy, see "Fluid therapy: Calculating the rate and choosing the correct solution."

Catheter placement and care

The veterinarian will determine which fluids to deliver and at what rate in ml/kg/day, ml/kg/hr, or ml/hr. The technician can then start administering the fluids, usually through an intravenous (IV) catheter. IV catheters are most commonly placed in one of three veins: cephalic, saphenous, and jugular—the cephalic vein being the most common in small animals. For details on how to place a cephalic catheter, see "Cephalic catheter placement."

Practitioners use several types and sizes of IV catheters. In most patients, a peripheral catheter is indicated. Packaging for these catheters lists a gauge number that correlates to the inside diameter of the IV catheter. The larger the gauge number, the smaller the catheter's diameter (i.e. a 22-ga catheter has a smaller internal diameter than an 18-ga catheter). The largest-diameter (smallest-gauge) catheter possible should be used when placing an IV catheter. The wider the catheter's diameter, the less resistance to the fluid flow, allowing for a fluid bolus to be administered more quickly.

Daily IV catheter care is extremely important. If an IV catheter is placed but fluids are not started, flush the catheter with heparinized saline solution every four hours to prevent clotting. It is important to remove the IV catheter's wrap so the insertion site can be visualized to ensure there is no redness, swelling, or discharge from around the insertion site. Check the patient's leg for any swelling above or below the catheter. If there is swelling, remove the catheter and place a new one in a different location. If catheter care is not provided, the vein may develop thrombophlebitis in which the vein becomes inflamed (phlebitis) and a thrombus (clot) is formed on the vessel walls. If left untreated, the vein may completely thrombose, causing a severe clotting in the vessel that will render the vein unusable and increase the risk of infection at the catheter site.

Before administering a solution through a fluid line port or directly into the catheter, swab the port with alcohol. When disconnecting a patient from fluids, always cap off the IV catheter and place a fresh capped needle on the end of the fluid line. Be sure to keep the connection between the IV catheter and the IV line sterile.

IV fluid pump and drip lines

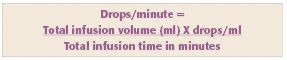

Most veterinary hospitals have IV fluid pumps that provide a set amount of fluids per hour. The use of IV fluid pumps is the safest and most accurate way to deliver fluids to a patient. If your practice does not have IV fluid pumps, IV fluids can still be administered by using IV drip lines, either via micro-drips or macro-drips. The micro-drip sets deliver 60 drops/ml, while the macro-drip sets deliver 10 or 15 drops/ml. The number of drops/ml can vary by manufacturer, so check the packaging to determine the number of drops/ml. Calculate the drip rate for the patient based on the drops/ml and the amount of fluids to be provided by using the formula above.

When providing fluids to a patient via a drip set, monitor the amount of fluid in the bag to ensure the patient is receiving the prescribed amount. Note that the patient's position can greatly impact the amount of fluids received. For instance, when a cat lies down and tucks its legs underneath itself, the fluids can stop flowing; but when the cat is moving, it may receive a large fluid amount in a short period. To help monitor the amount of fluids a patient is receiving, put a piece of tape beside the numbers on the side of the bag and note the amount of fluids left. Write at the top when the bag was started, and then mark off where the fluid should be at every hour after that.

Monitoring

Another important role for technicians is to monitor patients for signs of overhydration, or fluid overload. Disease processes such as cardiovascular disorders will make patients more prone to overhydration. In other cases, the cause may be iatrogenic. Technicians should monitor the patient for serous nasal discharge, chemosis, restlessness, shivering, tachycardia, coughing, tachypnea, dyspnea, pulmonary crackles, ascites, polyuria, exophthalmia, vomiting, and diarrhea. The patient should also be weighed on the same scale at least once a day. A gain or loss of 2.2 lb (1 kg) means an excess or deficit of 1 L of fluids.1 If the patient develops any of the above signs, notify the veterinarian immediately.

To treat fluid overload, discontinue fluid therapy and administer a diuretic (e.g. furosemide) to help remove the excess fluids from the body. If the patient is dyspneic, it may be necessary to provide oxygen supplementation.

Conclusion

Fluid therapy is a cornerstone of veterinary care and is often the difference between life and death. Providing safe, appropriate hydration and returning patients to electrolyte and fluid balance takes skill. Veterinary technicians are generally responsible for patient preparation and treatment plan implementation and must be diligent guardians of ongoing treatment and catheter care.

Brandy Terry, CVT, VTS (ECC), is the director of critical care and specialty nursing at Animal Critical Care and Specialty Group at the Veterinary Referral Center, in Malvern, Pa.

REFERENCE

1. DiBartola SP. Introduction to fluid therapy. In: Fluid, electrolyte, and acid-base disorders in small animal practice. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Saunders Elsevier, 2006:325-344.