Confidently identify parasites on blood smears

Read on for tips to help you prepare a readable blood smear and identify what you see.

It's the case of the unknown entity: You're examining a blood smear and are sure you've spotted a parasite. Then you pull out every book on the shelf to help identify what you're seeing. I hope this article will help you feel more confident identifying "the unknown" the next time you encounter it.

Smear prep and evaluation

Although identifying blood parasites from a smear can be difficult, certain steps can increase the reliability of your identification. First, it's important to understand that blood parasites are only found in peripheral circulation during certain times of the disease process. So infection does not always equal identification on a smear. Blood film evaluation is just one tool within the diagnostic testing arsenal. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is the most reliable and accurate method of diagnosis and should be used to confirm blood film results.

Gathering a thorough patient history is critical, especially when parasite infection is suspected. Animals that live outdoors, go outdoors, travel, or visit dog parks or day care facilities carry a higher incidence of infection because of exposure to vectors. Determining a pet owner's ectoparasite control program may further aid in ruling in or out possible exposure. Remember that immunocompromised patients are at higher risk for infection.

When preparing a blood smear, make the smear directly from the patient's blood and not from an anticoagulated sample. EDTA anticoagulant can increase the likelihood for stain precipitation as well as cause Mycoplasma species to fall off the erythrocytes. Prepare multiple slides and, if possible, include samples from both a capillary vein and peripheral vein. A long read area on the smear is your best chance to find parasites, and a feathered edge is helpful for trapping infected erythrocytes. Stain slides with both a modified Wright's stain such as Diff-Quik (Dade Behring) and new methylene blue, making sure all stains are fresh and clean. Rinse slides gently and completely with distilled water, and allow them to air dry thoroughly. Examine the slides on oil immersion. Be sure to leave some slides unstained for a reference laboratory to evaluate.

Hemoparasite infections

Blood parasites can be found in most regions of the United States; however, knowing which hemoparasites are prevalent in your area can aid in proper identification. Note that several blood parasites' names have changed. In an effort to help us keep up-to-date, both the old and new names are referenced below.

Anaplasma species

Facts

• Two species affect dogs, and both are transmitted by ticks or, rarely, through infected blood transfusions.

• Anaplasma phagocytophilum (formerly classified as an Ehrlichia species) is consistently found as a coinfection with Borrelia burgdorferi. Coinfection is more likely to result in clinical disease.

• Anaplasma platys is typically found incidentally when veterinarians are diagnosing thrombocytopenia.

Identification

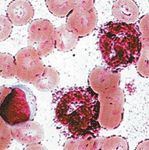

• These parasites are not found on erythrocytes. Anaplasma phagocytophilum is found within the cytoplasm of neutrophils, and A. platys is seen only within platelets. Because of that, they are located largely within the read area of a smear.

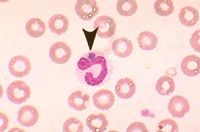

• Anaplasma phagocytophilum is seen as a large morula within the cytoplasm (Figure 1). More than one morula may be present.

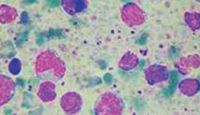

• Anaplasma platys appears as dark-staining granules within platelets (Figure 2).

1. Anaplasma phagocytophilum on a blood smear. Note the large morula in the cytoplasm (Wrightâs stain; 100x).

2. Anaplasma platys on a blood smear. The small dark-purple dots throughout the smear are A. platys within platelets (Wrightâs stain with Prussian blue; 40x).

Clinical signs

• Thrombocytopenia is a typical clinical sign of an A. platys infection.

• Anaplasma phagocytophilum can be acute or subclinical. Frequent clinical signs include fever, lethargy, inappetence, lameness, stiffness, or a reluctance to move. Mild splenomegaly and lymphadenomegaly can occur. Laboratory findings commonly consist of thrombocytopenia, lymphopenia, eosinopenia, and a mild anemia.

Treatment

• Therapy is the same for both species: oral administration of doxycycline (5 to 10 mg/kg once or twice daily for 28 days).

• Corticosteroid administration is not recommended.

Babesia species

Facts

• Nine species have been identified in dogs, but Babesia gibsoni and Babesia canis are currently the most common in the United States.

• Babesia gibsoni and B. canis can both be transmitted through ticks and, rarely, blood transfusions; however, B. gibsoni can also be transmitted dog-to-dog via bites.

• Babesia gibsoni is prevalent in pit bull populations, whereas B. canis is commonly identified in greyhounds.

Identification

• Piroplasms of Babesia species can be found within erythrocytes.

• Because of the increased weight of parasitized erythrocytes, they are often pushed to the feathered edge of the smear.

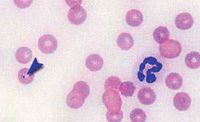

• Babesia gibsoni inclusions appear as small, pleomorphic ring-shaped organisms (Figure 3).

• Babesia canis inclusions are much larger than those of B. gibsoni. They are teardrop-shaped and often found in pairs (Figures 4A & 4B).

3. Babesia gibsoni on a blood smear. It can look similar to Cytauxzoon species (Figures 5A-5C), but B. gibsoni is exclusively seen in dogs, whereas Cytauxzoon species is exclusively seen in cats (Wrightâs stain; 50x).

4A & 4B. Babesia canis on a blood smear. It is common to find multiple piroplasms within one red blood cell (Wrightâs stain; 100x).

Clinical and laboratory signs

• Moderate to severe hemolytic anemia

• Thrombocytopenia

• Cyclic fever

• Hyperglobulinemia (seen as an elevated total protein concentration on a refractometer)

• Splenomegaly

Treatment

• Therapy is aimed at treating specific Babesia species, so correct identification is imperative.

• Babesia gibsoni infection is treated with atovaquone (13.5 mg/kg orally three times a day) given with a fatty meal, plus azithromycin (10 mg/kg orally once a day) for 10 days.

• Babesia canis infection is treated with imidocarb (6.6 mg/kg given subcutaneously or intramuscularly, repeated in two weeks). Premedicating with glycopyrrolate is suggested.

• Do not give prednisone until treatment of the parasitic infection is concluded.

Cytauxzoon felis

Facts

• This tick-transmitted intracellular protozoan affects cats.

• Cytauxzoon felis is typically seen during the spring and summer.

Identification

• The piroplasms are found within erythrocytes, commonly at the feathered edge of the smear.

• The inclusions appear as signet rings, comma-shaped, or elongated signet forms (safety pin). Multiple inclusions may be present within the erythrocyte.

• The inclusion will have a refractile appearance within the band portion of the ring (Figures 5A-5C).

5A-5C. Cytauxzoon felis on a blood smear. These inclusions have highly refractile centers (Wrightâs stain; 5A-40x, 5B & 5C-100x).

Clinical signs

• Signs of cytauxzoonosis are related to the disease stage. Unfortunately, this disease progresses within two or three days and is often fatal.

• Everything from lethargy, anorexia, dyspnea, icterus, and pale mucous membranes to high fever is consistent with infection with this blood parasite.

Treatment

• Quick intervention is necessary for any chance of recovery.

• Supportive treatment should be given as appropriate.

• To target the infection, cats should be given imidocarb (2 to 3 mg/kg intramuscularly) once a week for two weeks or a combination of atovaquone (15 mg/kg orally three times a day) and azithromycin (10 mg/kg orally once a day) for 10 days.

Mycoplasma haemofelis

Facts

• Mycoplasma haemofelis (formerly Haemobartonella felis) is an epicellular bacteria that may be transmitted by arthropod vectors (fleas), from queen to kitten, through direct cat bites, or through blood transfusions.

• Acute, recovery, and carrier states exist, and clinical disease is often seen in immunosuppressed cats.

Identification

• Mycoplasma species are seen well with new methylene blue stain.

• These bacteria are typically seen along the periphery of erythrocytes within the feathered edge of the smear.

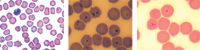

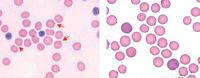

• They appear as extremely small cocci, rods, or rings with multiple bacteria per erythrocyte (Figures 6A & 6B). They are easily confused with Howell-Jolly bodies and stain precipitate (Figures 7 & 8).

6A & 6B. Mycoplasma haemofelis on a blood smear, which should not be confused with Howell-Jolly bodies (Figure 7) or stain precipitate (Figure 8). These very small epicellular inclusions are routinely seen on the edge, but inclusions can be seen on top of the red blood cell (Wrightâs stain; 6A-40x, 6B-100x).

8. Stain precipitate can interfere with identification of any blood parasite. Mycoplasma haemofelis would be impossible to identify under these conditions (Wrightâs stain).

7. Howell-Jolly bodies on a blood smear, which can be confused with M. haemofelis (Wrightâs stain; 40x).

Clinical signs

• Cyclic fevers, weight loss, and fatigue

• Acute extravascular immune-mediated hemolytic anemia, or acute hemolytic anemia (feline infectious anemia)

Treatment

• Supportive treatment should be given as appropriate.

• There is no guaranteed treatment, but to target the infection, cats may be given doxycycline (10 mg/kg orally once a day for 21 days) chased with water or enrofloxacin (5 mg/kg orally once a day for 14 days).

To become proficient at identifying all hemoparasites, you should look at both normal and abnormal smears often. You will gain experience in determining the difference among stain precipitate, normal inclusions, and invaders. Good luck in your search.

Melissa Andrasik, BS, RVT, is an adjunct instructor for Maple Woods Veterinary Technology Program in Kansas City, Mo.